June 27 - October 18, 2009

|

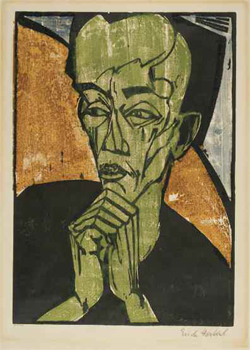

| Erich Heckel, Self-Portrait, 1919, color woodcut, Gift of Kate Butler Peterson, 2009.6 |

The fifth in a series of Worcester Art Museum installations explaining the techniques of printmaking, this exhibition considers the relief processes, including woodcut, wood engraving and linocut. The oldest and simplest methods of making a precisely repeatable image depends upon carving a printing surface, applying a film of ink, and stamping the pigment onto paper or fabric. With the development of the printing press in the fourteenth century, woodcut became the most common method of mass producing pictures in the West. In Japan, the process developed independently as a method for creating stylish color images of actors and landscapes. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, finer detail and block longevity were accomplished by wood engraving. Metal engraving tools were used to carve images in the end grain blocks of very hard wood, in a process that required great technical skill. By contrast, ease and simplicity were the goal of linoleum block printing in the early years of the twentieth century. Developed as a floor covering, linoleum was soft, and without the grain that makes wood tricky to carve.

This exhibition includes relief prints from around world, dating from the fourteenth century to the present. Among them will be prints after Albrecht Dürer and Pieter Paul Rubens. Color relief prints from Europe, Japan, and America will represent the development and gradual refinement of the media. Wood engravings by the English pioneer Thomas Bewick will contrast with the bright color linocuts of Vojtech Preissig, the Czech-born champion of this process in America. Carved printing blocks from wood and linoleum blocks, and cutting tools, will explicate the process of making a color relief print.

The earliest European prints on paper were practical and affordable, like playing cards and devotional images like Madonna of Wisdom. Sold at religious fairs and pilgrimage sites, these holy pictures were often hand-colored. Most seem to have been tacked up in homes and workplaces, so few have survived.

Block Books and Movable Type

Around 1460 German printers began to produce “block books,” for which the text and pictures of each page were painstakingly cut from a single piece of wood. Pictorial woodcuts were further integrated into book printing with the development of moveable type. Carvers made their blocks as thick as type, so they could be locked in the press together with text and printed in one operation. The burgeoning book printing and publishing industry determined a division of labor that long governed the production of woodcuts. Publishers provided financial resources for the projects, buying materials, engaging artists to design the images, and employing specialist wood carvers, printers, and book binders.

Chiaroscuro Woodcuts

The first color woodcuts were made early in the sixteenth century. Chiaroscuro woodcuts imitated the current manner of drawing in pen and wash on toned paper, with highlights drawn in white. In northern Europe, a supplementary tone block was used along with a customary line block, to print a muted color over much of the sheet. Grooves in this tone block allowed the white of the paper to show through and create highlights. An Italian variation of this technique was patented in Venice by Ugo da Carpi. He eliminated the line block, and represented light and shade with three or four tones of a single hue, each printed from a different block.

Japanese Woodblock Prints

In Japan, printmaking evolved as a popular, affordable medium. Ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world,” represent a realm of worldly pleasures, of stylish actors, fashionable courtesans and landscapes of dreamlike beauty. Instead of the oil-based ink and printing presses of the West, Japanese artisans employed water based-ink and printed by hand. They used brushes to paint color onto the blocks, and printed by rubbing the back of a moistened sheet of paper with a flat bamboo leaf pad. Multicolored woodcuts, printed from several blocks, were meticulously registered. Painting ink on the block for each impression, these artisans also achieved subtleties of hue and tone that are quite different from western prints. They extended their colors with rice paste, for subtle modulation and color blending. This tonal delicacy and the linear energy of Japanese design are apparent in the atmospheric landscape prints of Hiroshige.

Wood Engraving

Late in the eighteenth century, the process of wood engraving made it possible to print finer detail from longer lasting blocks. It had long been known that by cutting a block of hard material, like boxwood, across rather than along the grain, much finer lines were possible. These stony blocks were carved with a burin, the copperplate engraver's tool, to create fine white lines in the finished print. However, printing a clear image from such a block required great pressure that tore the soft paper. When hard-surfaced paper became available, wood engraving burgeoned. The leader of this development was the Englishman Thomas Bewick. End grain printing blocks could be only as large as the diameter of the box tree, so to make a large wood engraving, several small blocks were fastened together. Since thousands of impressions could be printed from an engraved woodblock, it was very practical method of commercial printing.

White-line Woodcuts

During World War I, a group of printmakers working in the artists' colony of Provincetown, Massachusetts, developed a streamlined way to produce multicolored prints from a single carved block. They combined their understanding of Japanese color woodcut with the principle of applying several colors to an etched plate to be printed in one pass through the press. The “Provincetown Printers” penciled a line drawing onto a pine plank, and carved them away in unadorned grooves. When they brushed watercolors onto the block, the grooves in the surface kept the pigments from mixing. By tacking the paper to one edge of the block, they could fold the sheet over the printing surface and back, assuring proper registration. The moistened paper was folded over the printing surface, and rubbed on the back to print, embossing unprinted white lines in the sheet.

Linoleum Block Printing

In the mid-nineteenth century, Frederick Walton developed and patented linoleum in the United Kingdom as a floor covering material. He mixed powdered cork with linseed oil, spread the emulsion onto burlap or canvas, and allowed it to oxidize and harden. Linoleum was a versatile craft material, ideal for relief printmaking. It is relatively inexpensive, and has a smooth, soft surface that is easy to carve. Linoleum is not as porous as wood, but viscous printing ink adheres well to its oily surface. This ease of use made linoleum block prints- or linocuts- ideal for the schoolroom, and for introducing students to printmaking.

Twentieth Century Innovation

Continued technical refinements continued in relief printmaking over the course of the twentieth century. Pablo Picasso used the process of reductive woodcut to make multicolored prints from a single block. After cutting a relief matrix and printing one color, he recarved the same surface and overprinted in another color, on the same sheet of paper. Thus, the reductive relief block is destroyed over the course of its use.

In calligraphy artisans created relief printing plates by gluing fabrics, paper, and other found objects to the printing surface. They often supplemented their collagraph plates with materials like gesso or modeling paste, which were plastic and workable at room temperature but dry to a hard surface that could be inked and printed.

Printmakers also took advantage of the progressive development of electric tools. They used electric drills, routers and powered chisels to carve their printing blocks. Late in the century, even computer controlled lasers were used to burn images into hardwood blocks, enabling artists to combine images of great precision with printed patterns from the grain of exotic woods.

The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated, didactic pamphlet, distributed free to the public, and funded by a gift from Bernard and Louise Palitz.

| Select Images from the Exhibition | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sign up for WAM eNews

Sign up for WAM eNews